Response to a paper published in LES ECHOS dated September 3rd 2010.

The question is whether to subscribe to an opinion expressed in Les Echos newspaper on 3 September 2010 according to which the first decade of the new millennium put an “end to the myth that shares are the best of all investments” and undermines the “postulate that this investment is superior over the long run”. Quite the contrary, it seems very premature to announce the death of the Theory of shares’ superiority. Readers need to be disabused of this confusing notion.

Firstly, shares’ long-term supremacy is neither a postulate (something that by definition cannot be demonstrated) nor a myth (a vision of the financial world that is not only false but also irrational).It is indeed a theory in all senses of the term: something that is descriptive insofar as it is based on market history analysis; explanatory; and above all predictive, since it is meant to inform investors. It is for this reason that the question of the theory’s validity is so significant in both scientific and practical terms.. Before any major pronouncements, however, we need to recall the origin of the idea, its underlying hypotheses and its limitations. The question being examined here is whether the Theory of shares’ superiority remains valid in the year 2010 - and if so, what lessons investors should draw from it.

The theory’s origin

This theory is based on an analysis of stock market databases that generally extend as far back as the year 1900, as illustrated by the graphic published in Les Echos on 3 September.

Without a shadow of a doubt, the key observation is that over a sufficiently long period in a capitalist country such as the United States characterised by controlled inflation (between 2 and 3% per annum), blue-chip stocks will generally produce an annual return of 10% before adjustment for average inflation levels of 3%. These observations underpin the development of a real hierarchy of investments ranging from shares (10% per annum before inflation) to money market investments (which merely follow inflation, thus ca. 3%) with property (7.5%) and 10-year state debt (5%) coming somewhere in between.

Theory of shares’ superiority: foundations and conditions of validity

According to the theory, “The performance of shares issued by large listed companies -construed as the sum total of dividends paid and changes in share prices from 1 January through 31 December – tends to average 10% per annum over the long run.”

The theory is based on two condition : an environment that is both capitalist and free market-oriented; and price stability subject to central bank supervision (and characterised by inflation rates of 2 to 3% per annum). Furthermore, it only applies over the long-term. Since 1900, Wall Street and London have corroborated the theory to a tee. France, on the other hand, experienced two high inflation periods during the first half of the 20th century and therefore does not satisfy the necessary price stability conditions. Thus, shares in France recorded annual rises (net of inflation) of 3% versus 6% in the United States. As for the lost decade (2000-2010) mentioned in Les Echos, the Theory does not exclude this possibilty (exemplified in the United States by the 1930s and the 1960s), particularly in light of the 20-year bull market (marked by annual rises of 20% between 1980 and 2000). Quite the contrary, the “lost decade” recalls one of the Theory’s corollaries, which is that share performance cannot exceed an annual pre-inflation growth rate of 10% over the long run.

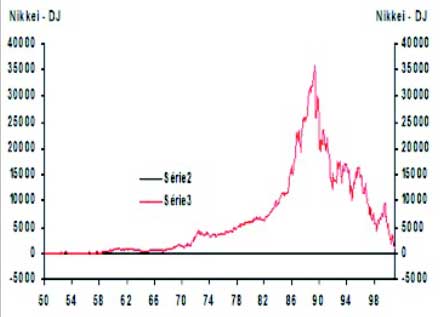

More than the French CAC-40 index’s lost decade, critics of the Theory will usually look at how Japan’s Nikkei index has evolved since 1990. This is a particularly spectacular counter-example, with the index having fallen from 40,000 in 1990 to ca. 10,000 in 2010. A quick overview comparing the Nikkei and the Dow Jones between 1950 and 2000 would suffice, however, to show the fallacies of this argument. Firstly, the indices were approximately at the same level in 1950 (500) and in 2000 (10,000), with the Dow having risen on average by 10% per annum over this period. Analysing the Nikkei’s comparative evolution is not particularly difficult in this light – it simply reflects the bursting of the gigantic bubble that had built up in Japan over the 1970s and 1980s (partially justified at the time by Japanese workers’ courage and productivity, their managers’ attributes, savers’ strong discipline, etc.)

Theoretical implications and practical consequences

So what lessons should investors derive from the Theory of shares’ superiority? One is a harbinger of good news - the other less so.

The good news is that despite the existence of “lost decades”, shares’ average long term performance was indeed plus 10% per annum. The bad news is that even the major blue-chip stocks are subject to this iron law of 10%. Whenever they try to break free from gravity, sooner or later they fall back to earth, i.e. in the 21st century as before, nemesis always beats hubris. Note the important corollary illuminated by Japan’s own two lost decades, to wit, the longer and the steeper that share prices rise, the harder they fall.

It is reasonable to predict, 20 years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, that for the next few decades the capitalist free market environment that large private sector companies require to thrive is safe in the world’s wealthier countries, and that the larger central banks - independent and competent institutions – will not fail in their mission of controlling inflation. The favorable macroeconomic conditions that the United States enjoyed during the 20th century are therefore, in the leading OECD countries, once again present in the early 21st century. Indeed, they may be more propitious than ever.

It is also noteworthy that in France today, the CAC-40 index more or less lags behind its main counterparts (Dow Jones and FTSE); 10-year French government bonds yield less than 2.5%; average share dividends only produce 4%; and property, the most competitive alternative investment, is still 40% over-priced (based on rental calculations)1. Furthermore, taxation is expected to evolve over the next two years in a way that will be damaging to assets that are fixed and therefore difficult to delocalise.

All in all, the conditions at present in the year 2010 are clearly ripe for Les Echos to be able celebrate, once September 2020 arrives, the “marvelous decade” that our stock market will have experienced … and the durability of the Theory of shares’ superiority that will have ultimately lost none of the prospective or practical powers that it already enjoyed back in 2010.

Prof. Dr (HDR) Eric PICHET